We’ve finally reached week six, with just five more sessions to go, then that’s it! The end was in sight. I wasn’t asking for much, just hoping that the side effects wouldn’t get significantly worse, and with just one final push, I’ll cross the finishing line. So I thought......

Yes, the week started well and I was keeping my fingers crossed, only for the gloopy saliva to change the trajectory. It somehow breached my defence and ambushed me one night, triggering some really deep coughs, which caused serious damage to my throat. Gone was the precious respite in the early hours of the morning when I often took advantage of reduced saliva flow and napped; it was difficult to rest properly. How bad was it? Well, in the worst two days, the painkillers didn’t work. Speaking to the radiotherapy receptionist to report for the day was more of a struggle than before. I also had to abandon my “survival diet” but lived on a few bottles of prescribed energy drinks each day. It took only 30 seconds to finish one bottle. Yes, 30 seconds, I could take it.

As the pain intensified, I wondered if it would worsen, well into the recovery period? My ibuprofen and paracetamol use was moderate and never reached the maximum daily dose. Should I increase the dosage, or try some stronger painkillers which act via different pharmacological mechanisms? Morphine has always been on my prescription for more effective pain relief, but I’ve been staying away from opioids and never used it. Being on my prescription didn’t mean that I could just pick it up from the hospital pharmacy though. I had the experience of trying to collect some mouth-rinsing salts from the pharmacy in the early days of radiotherapy, only to be turned away by the pharmacy staff because the prescription didn’t specify the date for the next dispensing and they were not allowed to hand out the medicine. It took me a while to get that sorted with a doctor, who was harder to reach during the pandemic. Now, such a date was also lacking on my morphine prescription.

I decided it’s time to give morphine a try. A radiographer once told me that many patients would start using codeine from the third week onwards, so it’s pretty unusual that I was still on common household painkillers. Anyway, I had to sort out my morphine prescription on Day 30 and make sure I took all required medicines home, since I would soon stop making daily trips to the hospital, and I wouldn’t want the hassle for my family to pop back to the hospital on a later date just to fetch some medicine.

I attended all previous 29 treatment sessions by myself. However, for the 30th —— the very last one, I was frail and barely speaking. I had to grab my sister along to help with verbal communications with the medical team, to ensure my prescription was correctly annotated (yes, the “dispensing from” date......) and all medicines were collected.

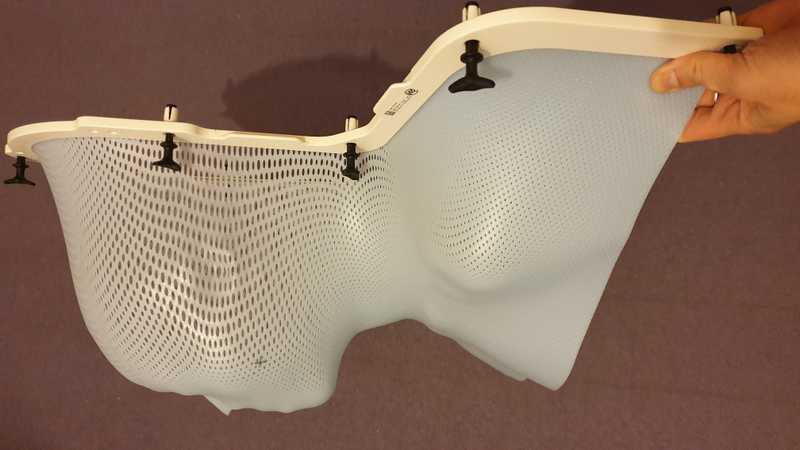

For six weeks, the only company I had during treatment was my bespoke mesh mask, which was stored in the therapy rooms for daily use. At the end of the regimen, a patient could choose to let the hospital dispose of the mask, or take it home as a souvenir. I heard that some patients have turned their masks into pieces of art, but I don’t think I have that kind of talent.

But still, I decided to bring my mask home. Not that I had any great ideas for a craft project, nor was I planning to hang it on the wall. I just somehow felt that the mask was like my double, and it felt “wrong” that it would be destroyed just like that......

So, before the finale, I said to the radiographer,

I’m bringing the mask home today.

“Ah, you can only do so after the very last session.” It’s difficult for radiographers to track where each patient was on their treatment journey, since they looked after so many.

Yes, today is my last day.

The radiographer quickly checked my records. “Oh yes, indeed!”

It’s time to introduce the community of radiographers who looked after and stood by me throughout those 30 treatment days. There were over ten of them in total and they always worked in pairs. Everyone was as nice as the medical staff in the ward, always wearing a warm smile and had answers to my questions. For example, it was the radiographers who explained to me how the 30 sessions were supposed to be identical, with the same radiation dose delivered at the same angle every single time (the oncologist didn’t cover such details). They were also the ones who took advantage of a short gap in their schedule one afternoon to show me my CT scans of the day with the shape and strength of the radiation field superimposed. The field was pretty wide actually, no wonder why the side effects were plenty.

In addition to carrying out their primary duty of administering radiation with precision (so as to minimise the side effects in patients), radiographers honourably took on extra COVID-19 risks by not shying away from having close contact with cancer patients. While it’s true that we (the patients) were all tested negative for COVID-19 prior to our regimens, and most of us weren’t that socially active, one couldn’t rule out the possibility of patients with weakened immune systems unknowingly picking up the virus during the multi-week regimens (especially in the early stages of asymptomatic infection). Why did it matter? Well, for every session, we had to remove our COVID face masks before being fitted with the mesh masks, and sometimes had to answer radiographers’ questions verbally when hand gestures didn’t suffice. Bear in mind those were the days when the vaccines were still under clinical trials and we're still two months away from the national roll out of the vaccines among medical professionals. So, there was a real possibility that radiographers could catch the disease from cancer patients.

Another point worth noting was the lack of screens or curtains delineating a changing area in the treatment rooms, perhaps as part of pandemic control measures to reduce common touchpoints by patients and staff. That probably wasn’t a big issue for male patients, but how about the ladies? Fortunately, the male radiographers all turned around and looked away as soon as they sensed that I had to take my top off, without anyone prompting. Did any of them peep? I couldn’t tell, as I had my back to them too. But in any case, there wasn’t much interesting to see, right? What I wanted to get across here is that I felt respected by the male radiographers’ spontaneous and appropriate gestures and there was not a single awkward moment. I’m grateful to the NHS for training these really professional male radiographers. In the wake of “Me too”, I was fortunate that at no point during my regimen did I have to worry about being taken advantage of, even when I was pinned onto the treatment table by the mesh mask. Just imagine what if things turned out to be the opposite. What should I do? Raise a formal complaint with the hospital? Yes, of course I could, but would I really have the physical and mental energy for it?

Right. The radiation bombardment finally stopped. It’s over.

The mesh mask was not only my intimate partner throughout the regimen, but also acts like the medal around the neck of a marathon runner as she crosses the finishing line. It recognises “mission accomplished”. Any patient leaving the treatment room with the mask in hand is a survivor.

I survived.

As my sister and I slowly strolled away from the radiotherapy department, the mesh mask attracted well-wishes and encouragement from medical staff passing by. To my surprise, I bumped into the radiographer who made my mask, and how nice that she recognised me too among all the patients she looked after. I remembered vividly her advice on the side effects of radiotherapy as she led me to the exit after the mask-making session: she said I should not hesitate to report them, because the whole team of radiographers would keep a close eye on them and take them very seriously. And seriously they did, even though for me western medicine didn’t help a great deal in alleviating them.

Another senior radiographer shared this from his team’s perspective: radiographers always witness how a patient becomes frailer and frailer during the course of treatment, eventually reaching rock bottom as the course ends, which is also the time to say goodbye; from seeing and looking after the patient every day to not knowing if they will ever meet again, there is an inevitable hint of sadness. While they all wish patients a speedy recovery, they rarely catch a glimpse of that part of the cancer journey.

Radiographers, thank you so much for looking after me. Goodbye for now, but I will be back for a visit. Yes, I really mean it. Just like the Queen said about the lockdown during the pandemic, “we will meet again.”